KEY

INFO

- - - - -

- - - - - - -

Born As: Alfred Joseph Hitchcock

Born: August 13, 1899, Leytonstone,

England

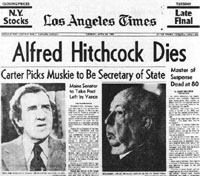

Died: April 28, 1980 from Liver Failure and Heart Problems

Education: St. Ignatius College, London; School of Engineering

and Navigation

(mechanics, electricity, acoustics, navigation); University

of London (art)

By Charles Ramirez Berg

The acknowledged master of the thriller genre he virtually

invented, Alfred Hitchcock was also a brilliant technician who

deftly blended sex, suspense and humor. He began his filmmaking

career in 1919 illustrating title cards for silent films at

Paramount's Famous Players-Lasky studio in London. There he

learned scripting, editing and art direction, and rose to assistant

director in 1922. That year he directed an unfinished film,

No. 13 or Mrs. Peabody . His first completed film as director

was The Pleasure

Garden (1925), an Anglo-German production filmed in Munich.

This experience, plus a stint at Germany's UFA studios as an

assistant director, help account for the Expressionistic character

of his films, both in their visual schemes and thematic concerns.

The Lodger (1926), his

breakthrough film, was a prototypical example of the classic

Hitchcock plot: an innocent protagonist is falsely accused of

a crime and becomes involved in a web of intrigue.

The acknowledged master of the thriller genre he virtually

invented, Alfred Hitchcock was also a brilliant technician who

deftly blended sex, suspense and humor. He began his filmmaking

career in 1919 illustrating title cards for silent films at

Paramount's Famous Players-Lasky studio in London. There he

learned scripting, editing and art direction, and rose to assistant

director in 1922. That year he directed an unfinished film,

No. 13 or Mrs. Peabody . His first completed film as director

was The Pleasure

Garden (1925), an Anglo-German production filmed in Munich.

This experience, plus a stint at Germany's UFA studios as an

assistant director, help account for the Expressionistic character

of his films, both in their visual schemes and thematic concerns.

The Lodger (1926), his

breakthrough film, was a prototypical example of the classic

Hitchcock plot: an innocent protagonist is falsely accused of

a crime and becomes involved in a web of intrigue.

An early example of Hitchcock's

technical virtuosity was his creation of "subjective sound"

for Blackmail

(1929), his first sound film. In this story of a woman who stabs

an artist to death when he tries to seduce her, Hitchcock emphasized

the young woman's anxiety by gradually distorting all but one

word "knife" of a neighbor's dialogue the morning after the

killing. Here and in Murder!

(1930), Hitchcock first made explicit the link between sex and

violence.

The

Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), a commercial and critical

success, established a favorite pattern: an investigation of

family relationships within a suspenseful story. The 39

Steps (1935) showcases a mature Hitchcock; it is a stylish

and efficiently told chase film brimming with exciting incidents

and memorable characters. Despite their merits, both Secret

Agent (1936) and Sabotage

(1936) exhibited flaws Hitchcock later acknowledged and learned

from. According to his theory, suspense is developed by providing

the audience with information denied endangered characters.

But to be most effective and cathartic, no harm should come

to the innocent as it does in both of those films. The

Lady Vanishes (1938), on the other hand, is sleek, exemplary

Hitchcock: fast-paced, witty, and magnificently entertaining. The

Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), a commercial and critical

success, established a favorite pattern: an investigation of

family relationships within a suspenseful story. The 39

Steps (1935) showcases a mature Hitchcock; it is a stylish

and efficiently told chase film brimming with exciting incidents

and memorable characters. Despite their merits, both Secret

Agent (1936) and Sabotage

(1936) exhibited flaws Hitchcock later acknowledged and learned

from. According to his theory, suspense is developed by providing

the audience with information denied endangered characters.

But to be most effective and cathartic, no harm should come

to the innocent as it does in both of those films. The

Lady Vanishes (1938), on the other hand, is sleek, exemplary

Hitchcock: fast-paced, witty, and magnificently entertaining.

Hitchcock's last British film,

Jamaica Inn (1939),

and his first Hollywood effort, Rebecca

(1940), were both handsomely mounted though somewhat uncharacteristic

works based on novels by Daphne du Maurier. Despite its somewhat

muddled narrative, Foreign

Correspondent (1940) was the first Hollywood film in his

recognizable style. Suspicion

(1941), the story of a woman who thinks her husband is a murderer

about to make her his next victim, was an exploration of family

dynamics; its introduction of evil into the domestic arena foreshadowed

Shadow of a Doubt

(1943), Hitchcock's early Hollywood masterwork. One of his most

disturbing films, Shadow was nominally the story of a young

woman who learns that a favorite uncle is a murderer, but at

heart it is a sobering look at the dark underpinnings of American

middle-class life. Fully as horrifying as Uncle Charlie's attempts

to murder his niece was her mother's tearful acknowledgment

of her loss of identity in becoming a wife and mother. "You

know how it is," she says, "you sort of forget you're you. You're

your husband's wife." In Hitchcock, evil manifests itself not

only in acts of physical violence, but also in the form of psychological,

institutionalized and systemic cruelty.

Hitchcock

would return to the feminine sacrifice-of-identity theme several

times, most immediately with the masterful Notorious

(1946), a perverse love story about an FBI agent who must send

the woman he loves into the arms of a Nazi in order to uncover

an espionage ring. Other psychological dramas of the late 1940s

were Spellbound

(1945), The Paradine

Case (1948), and Under

Capricorn (1949). Both Lifeboat

(1944) and Rope (1948) were

interesting technical exercises: in the former, the object was

to tell a film story within the confines of a small boat; in

Rope, Hitchcock sought to

make a film that appeared to be a single, unedited shot. Rope

shared with the more effective Strangers

on a Train (1951) a villain intent on committing the perfect

murder as well as a strong homoerotic undercurrent. Hitchcock

would return to the feminine sacrifice-of-identity theme several

times, most immediately with the masterful Notorious

(1946), a perverse love story about an FBI agent who must send

the woman he loves into the arms of a Nazi in order to uncover

an espionage ring. Other psychological dramas of the late 1940s

were Spellbound

(1945), The Paradine

Case (1948), and Under

Capricorn (1949). Both Lifeboat

(1944) and Rope (1948) were

interesting technical exercises: in the former, the object was

to tell a film story within the confines of a small boat; in

Rope, Hitchcock sought to

make a film that appeared to be a single, unedited shot. Rope

shared with the more effective Strangers

on a Train (1951) a villain intent on committing the perfect

murder as well as a strong homoerotic undercurrent.

During his most inspired period,

from 1950 to 1960, Hitchcock produced a cycle of memorable films

which included minor works such as I

Confess (1953), the sophisticated thrillers Dial

M for Murder (1954) and To

Catch a Thief (1955), a remake of The

Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and the black comedy The Trouble

with Harry (1955). He also directed several top-drawer films

like Strangers

on a Train and the troubling early docudrama (1956), a searing

critique of the American justice system.

His three unalloyed masterpieces

of the period were investigations into the very nature of watching

cinema. Rear Window

(1954) made viewers voyeurs, then had them pay for their pleasure.

In its story of a photographer who happens to witness a murder,

Hitchcock provocatively probed the relationship between the

watcher and the watched, involving, by extension, the viewer

of the film. Vertigo

(1958), as haunting a movie as Hollywood has ever produced,

took the lost-feminine-identity theme of Shadow of a Doubt and

Notorious and identified its cause as male fetishism.

North

by Northwest (1959) is perhaps Hitchcock's most fully realized

film. From a script by Ernest Lehman, with a score (as usual)

by Bernard Herrmann, and

starring Cary Grant and Eva

Marie Saint, this quintessential chase movie is full of all

the things for which we remember Alfred Hitchcock: ingenious

shots, subtle male-female relationships, dramatic score, bright

technicolor, inside jokes, witty symbolism and above all masterfully

orchestrated suspense. North

by Northwest (1959) is perhaps Hitchcock's most fully realized

film. From a script by Ernest Lehman, with a score (as usual)

by Bernard Herrmann, and

starring Cary Grant and Eva

Marie Saint, this quintessential chase movie is full of all

the things for which we remember Alfred Hitchcock: ingenious

shots, subtle male-female relationships, dramatic score, bright

technicolor, inside jokes, witty symbolism and above all masterfully

orchestrated suspense.Psycho

(1960) is famed for its shower murder sequence a classic model

of shot selection and editing which was startling for its (apparent)

nudity, graphic violence and its violation of the narrative

convention that makes a protagonist invulnerable. Moreover,

the progressive shots of eyes, beginning with an extreme close-up

of the killer's peeping eye and ending with the open eye of

the murder victim, subtly implied the presence of a third eye

the viewer's.

Later films offered intriguing

amplifications of his main themes. The

Birds (1963) presented evil as an environmental fact of

life. Marnie (1964),

a psychoanalytical thriller along the lines of Spellbound

showed how a violent, sexually tinged childhood episode turns

a woman into a thief, once again associating criminality with

violence and sex. Most notable about Torn

Curtain (1966), an espionage story played against a cold

war backdrop, was its extended fight-to-the death scene between

the protagonist and a Communist agent in the kitchen of a farm

house. In it Hitchcock reversed the movie convention of quick,

easy deaths and showed how difficult and how momentous the act

of killing really is.

Hitchcock's

disappointing Topaz (1969),

an unwieldy, unfocused story set during the Cuban missile crisis,

was devoid of his typical narrative economy and wit. He returned

to England to produce Frenzy

(1972), a tale much more in the Hitchcock vein, about an innocent

man suspected of being a serial killer. His final film, Family

Plot (1976), pitted two couples against one another: a pair

of professional thieves versus a female psychic and her working-class

lover. It was a fitting end to a body of work that demonstrated

the eternal symmetry of good and evil. Hitchcock's

disappointing Topaz (1969),

an unwieldy, unfocused story set during the Cuban missile crisis,

was devoid of his typical narrative economy and wit. He returned

to England to produce Frenzy

(1972), a tale much more in the Hitchcock vein, about an innocent

man suspected of being a serial killer. His final film, Family

Plot (1976), pitted two couples against one another: a pair

of professional thieves versus a female psychic and her working-class

lover. It was a fitting end to a body of work that demonstrated

the eternal symmetry of good and evil.

|